Post No. 5: Confesssional (Napasubò)

Dear Ben, Gelo, Minnie, Uncle Edgar, Edward, all of us...

My personal take on this thing we call art

I always thought I'd be an artist--a painter--until I was waylaid by poetry and literature. I "knew" what an artist was since I was always watching my eldest brother draw for the comics, paint on canvas, carve me a figure from soap or a toy gun from wood, or cut out an airplane from cardboard, just as I was always seeing my mother reading "pocketbooks" (Perry Mason, etc., but also Hemingway, Taylor Caldwell, and the bestselling authors of the time). Like all children, I learned to draw before I could write, but by fourth year high school, I was taught to read, as well as illustrate, Florante at Laura. I had a friend since the elementary grades with whom I would compete drawing komiks from our own stories imitating Prince Valiant or the Knights Templar or Flash Gordon and the fascinating reaches of outer space and the space ships that traversed the dark distances. In the talk balloons were my first attempts to write in English.

The world of literature (by the time I was in college) was a greater challenge for me as I literally taught myself poetry, trying to understand Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams, and later T.S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens (and all the authors and poets I later discovered for myself). Except for (or because of ) two great English teachers in high school (Divine Word College in Legazpi City), Mrs. Navea for grammar, Miss Reyes for literature and poetry, and Mr. Llamas who enjoyed reading my answers for the essay-type exams in college in the same institution, I never had a strict and formal training in poetry. (I never went to a Manila university although I passed all the entrance exams but both mother's overprotectiveness for a youngest son and our short finances for a Manila education kept me in the province. I'm both complaining and bragging...).

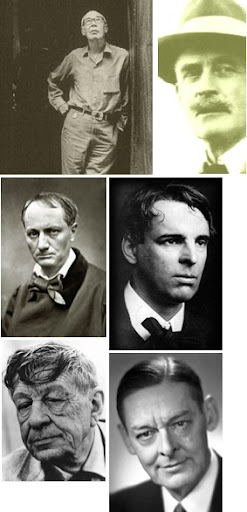

(My favorites, among many: the irrepressible Henry Miller; Knut Hamsun who wrote Growth of the Soil; and the poets Charles Baudelaire, William Butler Yeats, W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot)

(My favorites, among many: the irrepressible Henry Miller; Knut Hamsun who wrote Growth of the Soil; and the poets Charles Baudelaire, William Butler Yeats, W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot)I built my own reading list with authors name-dropped by other authors (the most notorious name-dropper was Henry Miller, who lead me to Baudelaire and the French impressionists, the Norwegian Knut Hamsun, Sir James George Frazier, name-dropped by Eliot as well, etc., etc.).

The more I went into literature, both by reading and by my attempts at creating my own poetry, the more I found that the other arts are as important, or that they fed into each other like rivers. In the meantime, I was reading philosophy by attending the classes of the theology majors, the secular would-be priests who studied in our school. I was reading history, Filipino and Philippine studies and literature, while cultivating my own love for music—appreciating the classics while always looking for the music that was seldom heard on radio—from Bach to the Beatles and Dylan and Sinatra and Miles Davis and Buencamino and Lucio San Pedro, and everyone in between, while studiously avoiding disco. I was trying to avoid being dictated to by the music industry. Still, all this lead to that main river called Art, or the life of the mind, and as I developed my tastes, whether it was in literature, music, the movies, etc., I kept looking for that something or someone who could teach or educate me further. The author that stimulated me, I looked for more of his books; the director, singer or even the photographer who interested me, I would track down as much as possible their works. Why are they good? was the question. What makes them better than the others? If I didn't understand them at first encounter, that didn't stop me from a second attempt at understanding or appreciating their works, which invariably lead me to wonders as yet undiscovered by myself.

Perhaps this entailed some boldness or courage on my part. The urge or instinct to discover and not to fear the unfamiliar inevitably leads one to discover that the good or better work of art is always different from the ordinary (that's why they are extraordinary). It is different not because it simply wants to be different (or is accidentally different) but because it is the result of a constant passion to be better than itself, or to be better than what it intended to be at the start. Thus, too, good art is never indifferent. The fine work of art, whether it is a poem or a photograph is always itself a discovery, not the result of discovery but itself the process of discovery. In a sense, the better poem or photographic image is always discovering itself, thus taking the reader or the viewer along the process. If it is good enough, there is always something new that the reader or viewer finds every time he reads or looks at it. The better story or song surprises even its author or composer—where it led which he probably never saw at the start.

The process is also one of selection that develops its own logic as it goes along, like the point of view or the photographic frame. Each artist has his own viewfinder in looking at the world. And when the reader or viewer finds himself in the point of view or frame of the artist, there occurs the felicitous confluence of two or more individual mind-eyes or heart-minds sharing a view of the world. Because it entails elements of persuasion, instruction and pleasure (after the painful creative struggle and the pain of going out of oneself to view the world from a point that is initially not one's own), it is both an esthetic and ethical experience. Dulce et utile, so Aristotle said. Delightful and useful... But delight (joy, pleasure, happiness), is its own usefulness. That is what art gives us. That is why we make art, whatever the medium or implement—words, images, shapes, tunes, pens, brushes, computers, cameras, Putosyap.

This, in a sense, is what we all do. Like the singular moment we caught the light streaming down the orange (or peach?) wall of a wash area, with the other shapes, shadows, colors, textures and surfaces framing the moment, or my own attempt at "framing" with lines and surfaces Edward A's mood without, inadvertently, showing his face (I hope he likes it), which are all perhaps informed by that encounter (our banggaan) between spontaneity and deliberateness which we like to call inspiration. When we inspire or are inspired, we breathe the air and rhythm of the universe. We glimpse, for one brief shining moment, why we are in it.

This, in a sense, is what we all do. Like the singular moment we caught the light streaming down the orange (or peach?) wall of a wash area, with the other shapes, shadows, colors, textures and surfaces framing the moment, or my own attempt at "framing" with lines and surfaces Edward A's mood without, inadvertently, showing his face (I hope he likes it), which are all perhaps informed by that encounter (our banggaan) between spontaneity and deliberateness which we like to call inspiration. When we inspire or are inspired, we breathe the air and rhythm of the universe. We glimpse, for one brief shining moment, why we are in it.Thank you for going through this rambling monologue, which in any case is part of Banggaan's rambling conversation. It's a still life watercolor / Of a now late afternoon... (thank you, too, Paul Simon, for being, like us, still crazy after all these years.)

Marne

Post No.6: How about 'offensive' art?

ganda ng kwento mo marne. onga laging discovery ang nangyayari at minsan nga yun mismong author ay nagugulat sa kanyang nadiskubre.

tanong ko lang tungkol dito...

“But delight (joy, pleasure, happiness), is its own usefulness. That is what art gives us.”

kailangan bang laging delight and joy ang binibigay ng art? kung nakaka-offend ba ang piyesa, art pa rin ba yan?

Gelo

Post No.7: Meat, poison, napalm

Gelo,

Delight and joy (I think) should be the ultimate results of the esthetic experience.

Let me hazard a guess about "offensiveness" in art. The offensive or the pleasant is defined from the physical to the biological to the spiritual spheres of life, meaning from chemical, to cultural, to anyone's notion of the Spirit (sex, ecology, and spirituality, according to Wilber). So offensiveness or pleasure or other valuations and categorizations can vary from the individual (chemistry, sex, biology), to the ecological (the ecologies of gender, family, society and the environment), to the realm of the Spirit (cosmic, the Deity, the God of all moralities and cultures, transcendental experience). Sorry, pasensya na, I have to explain myself...

Each and all of these are included in or included by one or the other, the biological included in the ecological, the ecological included in the Spiritual, and so forth. Everything is part of everything in a chain of growing complexity. If you remove the most basic hierarchy (the wholes in wholes), according to the theorists and advocates of evolutionary consciousness, the hierarchy above it collapses. E.g., the molecule cannot exist without the atom, the rock cannot exist without the molecule, etc. But atoms exist even if there are no molecules or rocks. Or, the "evolved consciousness" of the rock exists within or is still "lower" than the "more evolved" consciousness of the ahas which hides among rocks. But, both are parts of the physical (atoms, molecules, chemicals) realm, while only the snake is part of the biological (sex, reproduction, predation, survival), although, again, the physical realm is within the snake (atoms, molecules, venom or poison). So even in the "lower" realms, "offensiveness" is relative: atoms can collide (violent and "offensive," but which probably started the Big Bang), the snakebite kills rodents and people (the survival of the species of poisonous snakes may be threatened if they did not have their special chemical; and rats might threaten the harvest of crops if there were no snakes, and so forth.)

So offensiveness, or the experience of displeasure, or pain, "evolves" in complexity or definition according to the level of existence, like the saying "one man's meat is another man's poison." Although, one's own (conscious) level of evolution should tell him the difference between poison and meat, but with the wisdom to know that meat (nourishment from animals one kills in order to survive) co-exist with poison (death to us but survival to the snake). Is this getting sooo far away from art? Maybe not. More patience and indulgence please...

So. Perhaps. What is initially offensive (not pleasurable, may even be painful) in art may actually be a doorstep to some realization (delight). Such that, Picasso's Guernica, for example, is so violent that it can actually scare children, but it also reminds us how violent war is and in the end protests the violence of all wars. Can men or states exist without wars? Despite the history of "civilization" (conquests, subjugation, colonization, racial and cultural plunder and annihilations, from the Persians to the Romans to the Americans), indicating that nations must prosper and survive only at the expense of other weaker nations, men can still perhaps exist or survive without wars. Because no one man or state has ever tried it.

So. Perhaps. What is initially offensive (not pleasurable, may even be painful) in art may actually be a doorstep to some realization (delight). Such that, Picasso's Guernica, for example, is so violent that it can actually scare children, but it also reminds us how violent war is and in the end protests the violence of all wars. Can men or states exist without wars? Despite the history of "civilization" (conquests, subjugation, colonization, racial and cultural plunder and annihilations, from the Persians to the Romans to the Americans), indicating that nations must prosper and survive only at the expense of other weaker nations, men can still perhaps exist or survive without wars. Because no one man or state has ever tried it.Still, art does not "function" like a surgical tool (it cannot excise infected tissue in order to cure). It is a spiritual and evolutionary process. That's why no amount of the goriest or saddest photographs of children being napalmed in Vietnam could not stop LBJ from the "escalation" in the 1970s, and the daily bloodshed on TV cannot stop Bush or the military industry from sending more soldiers and equipment to Iraq. Even if, the images on film, video, photography and war reports have been brought to the level of art.

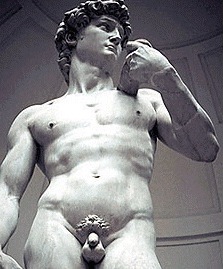

Okay. One more niggling question from Art History and Philosophy 101 (indulge me still, please, para hindi makalimutan, at para mapag-usapan ulit). How about pornography and nudity? Again, relative values from relative cultures, points-of-view, etc. Kung minsan, pagsinabing sina Boticelli and Michelangelo, etc. were always showing breasts and uncircumcised penises in their paintings and statues, and that the human body is a thing of beauty, it can become an excuse. Still, it is ultimately the truth. When Duchamp "vandalized" the Mona Lisa, was it offensive? Or maybe he was "making a statement" that in the end confirmed what we already knew but were afraid to ask. That perhaps perhaps values change (or don't change) when we look at them, that maybe irrationally, ugliness can exist side by side with beauty...

Okay. One more niggling question from Art History and Philosophy 101 (indulge me still, please, para hindi makalimutan, at para mapag-usapan ulit). How about pornography and nudity? Again, relative values from relative cultures, points-of-view, etc. Kung minsan, pagsinabing sina Boticelli and Michelangelo, etc. were always showing breasts and uncircumcised penises in their paintings and statues, and that the human body is a thing of beauty, it can become an excuse. Still, it is ultimately the truth. When Duchamp "vandalized" the Mona Lisa, was it offensive? Or maybe he was "making a statement" that in the end confirmed what we already knew but were afraid to ask. That perhaps perhaps values change (or don't change) when we look at them, that maybe irrationally, ugliness can exist side by side with beauty... Perhaps (because again it is relative), the only pornographic or evil thing about nudity and explicit sex on film or art is how much exploitation is involved for someone else's profit or advantage, and at the expense of another. Are FHM or Penthouse (meron pa ba nito?) more exploitative of women than Playboy?

Or put another way, when the dominant economies of the world (U.S. and the WTO) exploit the lesser economies--via lopsided trade agreements and policies on mining and exploitation of natural resources, and the breaking down of the small countries' last barriers of protection for economic survival—isn't this as pornographic as any smut magazine? Are the stories and pictures of children dying of famine, or of small farmers and manufacturers losing their livelihoods because of globalization, offensive? They will be only if we think that they intrude into our TV dinners.

But if they lead us to think about and question the world economic structure (or any other structure in the world) that results in global hunger and the plunder of weaker economies, that wars are mounted not so much for defense or the preservation of democracy but to impose systems and to preserve or gain economic power (precisely the negation of democracy)... then the realization, the knowledge that something has to be done to stop this unfairness in the world is still some kind of "ethical pleasure." Because this leads to choices and decisions, whether in the esthetic and contemplative realm of our art, or in our practical day-to-day actions.

Ay, sori, napadaldal na naman ako. Kasi, I have a little time to contemplate between two hanapbuhay projects. Hehe. Pasensiya na mga 'igan. If I start boring you, give me an electronic kick in the... derriere.

Marne

(to be continued)

No comments:

Post a Comment